The Legal Solutions to Image Manipulation (Part 4 of 5): This article is the fourth in a series prepared for The 13th Annual International Conference on the Image, “Here Comes the Metaverse: Designing the Virtual and the Real.” My presentation is entitled: Seeing is Believing: The Ethical and Legal Ramifications of Digital Image Manipulation.

WHERE THE WILD MANIPULATION GROWS

In my earlier articles in this examination of photo manipulation (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3) (alternative links to Part 1, Part 2, Part 3), I have ignored who paid the photographer. Where the photographer stood and when he or she pressed the shutter are arguably also manipulation, but I have ignored on-site timing, angle or subject choices; depth or field or lighting decisions; and all the intricacies that go into making an image. I have also set-aside post-production staging (how the images are presented) and captioning. Although we should consider these aspects as elements of image manipulation, I focused this series solely on the processing of the photograph into a tangible image.

And in this article, I say: There should be a law! But when, and to what images, should the law apply? Perhaps when the manipulation is so drastic, the image is no longer a photograph.

If we accept the digital camera is a data-collection device, the image does not exist until the photographer converts the RAW file using photo-editing software. Therefore, producing the digital image requires (arguably) processing beyond what a film photographer was required to do to a negative.

The question becomes: When is a photo no longer a photo?

DIFFERENTIATION

The standard response is when what is depicted in the ultimate image is grossly dissimilar from the physical reality depicted. Removing a wart or acne or fixing flyaway hairs does not create an image grossly dissimilar from the physical reality depicted. Removing wrinkles? Perhaps it depends on how severe the change is. Removing an object? Removing a person? Adding a person? And this is where we split hairs.

What is grossly dissimilar?

Grossly dissimilar would mean the image no longer resembles what is real or misrepresents what was depicted. I instinctively default to and offer you the legal, objective, reasonable person standard. We use the standard across tort law to describe the manner in which a reasonable person, in the same or similar circumstances, with similar experience and knowledge, would act. So, we ask: Would a reasonable person deem the altered image grossly dissimilar from the physical reality?

For a memorable example: John Paul Filo manipulated his famous photo of the Kent State Massacre, capturing May Ann Vecchio screaming over the dead body of twenty-year-old Jeffrey Miller. Filo removed a pole that appeared behind Vecchio’s head. He decided it was a distracting element. Would a reasonable person find that image grossly dissimilar from the physical reality? Yes, the manipulation altered physical reality, but I don’t think the resulting image was grossly dissimilar. The removal of the pole did not change the essence of the image. What do you think?

World-famous photographer Arnold Crane stated: “A digitally manipulated photograph is an illustration, not a news photograph. But some alterations are alright. You can remove an [obscuring] highlight or a reflection in a window, but you can’t remove an object. And you can’t change the meaning of a photograph.” So, perhaps in a documentary context, for photojournalism, removal of the pole, the object, may result in a grossly dissimilar image.

I focus on Crane’s notation that the alteration must change the meaning of the photograph to transform it into an illustration. For our discussion, I’ll call this reasonable person standard the Too Many Nuts Standard: Has the image of the brownie been altered to show more nuts than in the boxed recipe? The brownie company wants to increase sales without adding more walnuts to the boxed mix. A mere neophyte digital artist can add walnuts to the image decorating the box and enticing consumers. A reasonable person would deem that image grossly dissimilar from the physical reality when the brownies were not as nutty as depicted. Edits that violate the Too Many Nuts Standard take a photograph into digital art. We have an image that is no longer a photograph. The image is grossly dissimilar from physical reality.

Consider this example. A photographer captures images of throngs of beachgoers on a hot summer afternoon. If she processes the image from the RAW file by adjusting the exposure for flare, tweaking the white balance, and cropping out the boardwalk to focus on the people, the image remains similar to the physical reality. It’s a photograph. However, if she removes and adds people, uses high resolution to change the water to a dark blue, removes litter, puts kites in the sky… the result is an image that is grossly dissimilar from reality. The image is no longer a straight photograph. It is digital art.

But when does the transformation of photograph to digital art matter?

OBJECTIVISM AND SUBJECTIVISM

One of the counter-arguments to concern over image manipulation is subjectivist: that no objective reality exists. It’s okay if they depict the model with a waist that would not permit internal organs. Or if a journalist is creative with her photos. Essentially, subjectivists argue raising the camera to one’s eye and pressing the shutter is inherently subjective, so what does it matter? You may take one angle; I choose another. You crop out the burning building; I keep it.

Magnum photographer Peter van Agtmael stated in reaction to an image manipulation scandal: “There were a lot of loaded words like ‘truth’ and ‘objectivity’ being thrown around… I don’t really believe in these words. I’ve never met two people with the same truth. They are nice words, but remain aspirational and cloud a more nuanced interpretation of reality and history. We shouldn’t mistake something factual for something truthful, and we should always question which facts are employed, and how.”

However, as van Agtmael continues and makes clear, we cannot confuse objective and subjective with truth and deception. As I stated in the last article, facts depend on the proffer. I can use a zoom lens and it appears the woman is next to the table in the restaurant. You use a wide-angle lens and she is fifty feet away from the table. Both photographs are factual, but which is truthful? As long as the photograph is not deceptive, it is acceptable.

INTENT

Perhaps we can perfect our approach using Aristotle’s sage wisdom. In Rhetoric, the philosopher offers the manner in which we can judge persuasion as ethical or unethical. He says: If it is urged that an abuse of the rhetorical faculty can work great mischief, the same charge can be brought against all good things (save virtue itself), and especially against the most useful things such as strength, health, wealth, and military skill. Rightly employed, they work the greatest blessings; and wrongly employed, they work the greatest harm.

What if we judge images under the same standard? We merely need to determine whether the creator’s intent was malevolent or benevolent. The experts agree. Image manipulation is unethical when the changes represent reality inaccurately in order to deceive or mislead the viewer.

Consider what lawyers call mens rea: the state of mind or intent behind a criminal act. A person cannot be guilty of a wrong if he or she did not intend to do wrong. Most legal constructs differentiate along a continuum of acting with purpose and making a mistake. If a photojournalist intentionally adds people to an image to create a riot, the act is unquestionably deceptive. But what if that photojournalist adds a few people just to balance the composition? Arguably, the manipulation of the image is knowinglydeceptive: The photojournalist should know the addition of the people could cause viewers to deem the gathering a riot. Alternatively, if the photojournalist adds a few people to balance the composition but doesn’t inquire how the image will be used, the act is reckless. (Or, at the very least, negligent.) The photojournalist is not acting reasonably if altering a documentary, journalistic, image. Deception is present.

CONTEXT

However, not every photographer is a photojournalist charged with documenting a moment.

All communication happens within a context. As visual communication, we offer all images within a context. Context alters our interpretation of whether the intent was deceptive.

I edit Missus Jones’ portraits to remove all her wrinkles and neck waddle. Would a reasonable person find that image grossly dissimilar from physical reality? Yes. Is the intent of the manipulation to deceive? Yes. If the portrait is to hang in the Jones Family’s home, then who is harmed? No one. The family and friends all know she has a saggy, wrinkled face. But if the portrait is to be used for a dating profile where Missus Jones is representing herself as twenty-years younger, deception is present and harm is an eventuality.

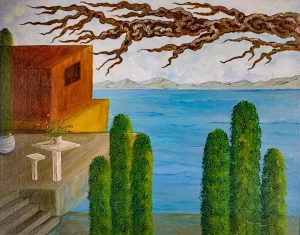

Similarly, if the image presenter creates a beach scene to sell as art, the intent to alter the reality into a grossly dissimilar image is not deceitful. It’s creative. The presenter knows the observer — however casual — admires the image as a creative work. However, if the image presenter is a journalist charged with documenting a scene, the intent to alter the reality into a grossly dissimilar image is deceitful.

If the photographer is a photojournalist, and representing the image as reality, she should document, not create. The transformation matters. If the photographer is an artist, the manipulation is desirable and expected. If the photographer is representing her work as a photo versus digital art, it matters. We must, then, examine the receiver’s understanding within the context. What does the potential paramour expect? What does the art consumer expect? What does the news consumer expect?

Our Too Many Nuts Standard must apply where: (1) the intent is to deceive and (2) harm can result.

So, what do we do about it?

LEGAL ROUTES

Perhaps legislation solves our image manipulation crisis. In the United States, and other countries, many criminal and civil laws already on the books can help victims of image manipulation.

Copyright infringement is an original creator’s route to remedy. Arguably, infringement covers any use of another’s photographs without remuneration or agreement. However, fair use exceptions to infringement exist — so the accused infringer could argue the altered image is for creative, educational, or critical purposes. Infringement actions are also difficult — or impossible— to prosecute internationally. And, as you must have concluded after reading the articles in this series, copyright infringement is only the tip of the image manipulation ice berg.

With deepfakes, privacy law covers numerous actionable torts. A victim of a deepfake could argue appropriation of likeness or right to publicity if the user gains a commercial advantage (makes money). A victim could also claim false light or defamation. And a victim could also sue for intentional infliction of emotional distress. Again, each of these routes has particular requirements and barriers to recovery. While it is easier for a private person to prove these claims, a public figure may have a difficult route arguing any of these torts if the user claims that the use falls under newsworthy (a public concern) or parody exceptions.

What about images presented at evidence in courts of law? In that case, the legal route is the only route. We must amend evidence procedural rules at all government levels to include image authentication prior to admission in any legal arena. As anyone can alter metadata encoded in the image, authentication would mandate the photographer to testify to all the aspects of the session, development, and production of the image.

With advertising, consumers have some routes to remedy a violation of the Too Many Nuts Standard. Although the United States has long-standing statutes against misleading or deceptive advertising, the mandates do not go far enough and are often only enforced against verbal violations. The fashion industry’s representation of the human body is not considered as deceptive as too many nuts in the brownie photo. One author argued, in the United States, a parens patriae (parent of the country) approach is warranted to regulate photo manipulation (retouching) through legislation.

As discussed in the prior articles in this series (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3), commercial manipulation and the financial loss it causes, although damaging, is not as dangerous as societal manipulation. As part of the effort to control misinformation, many national governments have implemented laws to control image manipulation’s negative societal effects. Norway, for example, requires advertisers and social media influencers to label retouched photos. France has followed with its Photoshop Law: Using Photoshop (or similar) is illegal if not fully disclosed. Violators face six months in prison and a fine of 75,000 Euros. (See Art. L. 2133–2 of the French Public Health Code.) Israel imposed a similar law in 2012 and requires advertisers — domestic or foreign — to post notice and reason for any image manipulation with the ad. The issue is largely ignored as the law contains no enforcement provision. Only a consumer can sue for a violation.

Other government initiatives include:

- Investigation and public education of deepfake technology

- Disinformation combat units

- Revocation of broadcasting rights

- Shutting down the internet.

FREEDOM

We must pause, however. With a nod to George Orwell, we cannot trust the government to apply its own policies to itself. And, any government control of communication or the arts raises free speech questions. Even a well-intentioned governmental effort can be too broadly enforced. For example, a government imposes a notice requirement for allmanipulated images. Will artists need to use such a notice? That depends on how the government defines art. And a government asserting control over what is and what is not art is a dangerous slope upon which to slip.

While some countries’ restrictions on free speech are well-known or obvious, image manipulation will test even countries who boast respect for speech freedom. How can a government draw a line on what is protected and unprotected? Is a digital artist who claims his work is photography committing fraud? Is a photojournalist who doctors images to make it seem a political candidate acts inappropriately subject to government regulation? These examples sit within the zone of creative and commentary — long-protected as free speech.

The United States Supreme Court has never explicitly ruled a photographer’s First Amendment rights. However, the court has historically interpreted speech to include images as communication. Even if we proceed with the Too Many Nuts standard, falsity alone does not remove First Amendment protection. The United States limits any control of speech to fighting words, inciting a riot, obscenity, and fraud. So, aside from false advertising or tortious acts, how would any government, while respecting free speech, impose meaningful restrictions on manipulation?

Yes, that question is a leading question. No government can both respect free speech and curtail deceitful image manipulation.

Are you willing to take personal responsibility?

References are embedded within the article, and you can peruse the complete list of resources here.