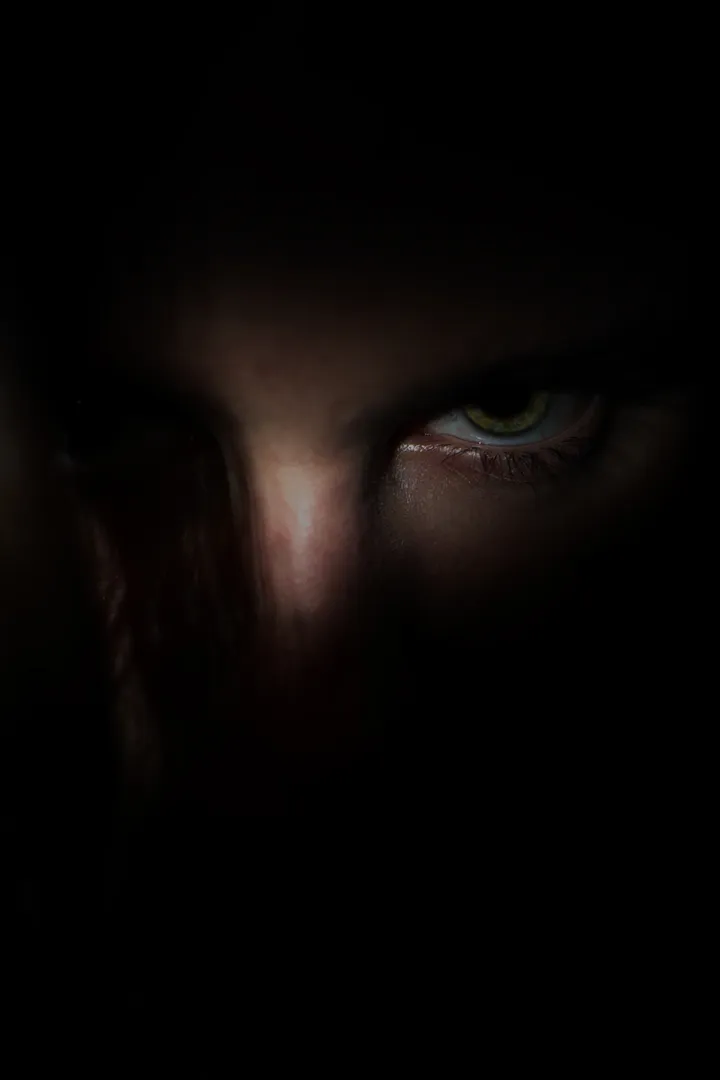

Protect yourself from the Evil Eye

SCENE 1

In 1922, Josephine Neri lived with her Italian-immigrant family in Danbury, Connecticut. The family, poor working-class, had arranged to relocate to New Jersey, where they planned on starting a business raising chickens on a large farm. All their worldly possessions were packed in their old wagon, which was parked in their barn.

That night, the barn and everything they owned burned to the ground.

They moved to New Jersey with nothing but the clothing on their backs. Cecilia Neri, Josephine’s mother, in tears that night and for years after, proclaimed the loss was the result of the “evil eye.”

SCENE 2

Josephine Neri Mastroianni, now married with her second child, Cecilia Marie, lived in a small apartment in the Bronx in 1945. She had this to say:

“The old woman next door came to visit to see Cecilia. She gazed into the cradle and she smiled. So nice a smile. She said, ‘Beautiful. What a beautiful child.’ I don’t know. Maybe she meant well. Then the baby got very sick — such a high fever. I had to call that woman — I forget her name — the one who used to come to do the ritual to rid the house of the malocchio — the evil eye.”

MALOCHHIO

What is this malocchio? Malocchio (pronounced mal-awe-kya) is the Sicilian-Italian term for the evil eye. Italians believe if someone knowingly and willingly, or in passing and unknowingly, envies what you have or what you gain, the jealousy turns into a curse of sorts, which then results in some sort of unexplained loss or harm.

Josephine had told me these stories many times. She is my maternal grandmother. Cecilia is my mother. I was raised on the premise that there are people out there who are jealous — people who feel angry or hurt at one’s gains.

As an educated American (in fact, the only woman in the Mastroianni line to ever to attend college) I began to question this belief and the symbol I wear around my neck to ward it off.

Belief in the malocchio seems easily understood. Unexplained tragedies befall helpless and confused people. To gain a causative view, a sense of control, and not to feel so tramped upon, a people may develop the idea that someone wished them bad luck.

Dominick Mastroianni, Josephine’s husband and my grandfather, in a heavy Sicilian accent, commented,

“It’s been around the world for all ‘a tiempo — you know what I tell you? This is something everybody he knows. In the Italian paper — I could show you — there’s the whole page on the back where the gypsies advertisement to get rid of the malocchio for the lira.”

Obviously, this survival lore is still used to explain what an innocent and unsuspecting victim cannot explain.

Malocchio translates as “bad eye” or “sick eye.” Perhaps someone with an eye problem — whether disfunction or deformity — looked at someone who was beautiful or who had earned something good (maybe won “the girl’s heart”) with envy. The victim, following the downfall in luck, must have blamed the malocchio. This is a logical assumption. Yet, the belief stretches further.

The curse comes in the form of excessive compliments — especially if that praise appears to be unearned or misplaced. You open a new business. The perpetrator goes on and on with how you will make a million dollars this week. Or you get a new job as a receptionist and the perpetrator praises you as a genius and that you will make the company a billion dollars and become famous. Maybe even the owner. Perhaps you get engaged and the perpetrator talks about your future: you will have healthy twelve children and enjoy your life together for a hundred years.

The raving compliments are suspect.

This is why many Italians give a compliment with the tag: God bless you. It’s meant to protect against even an accidental malocchio.

AROUND THE WORLD

The Evil Eye lore is said to have originated in Egypt, or, perhaps, Mesopotamia. Those in Turkey (where it’s called Nazar), India (where it’s called Drishti), part of the Middle East, Greece, Spain, Poland (where it’s called Zle Oko), The Caribbean, and Latin America (where it’s called Mal de Ojo) hold a similar belief. Scholars estimate at least 40% of the people on this planet believe in some form of the evil eye.

The Quran states:

“Say: ‘I seek refuge with the Lord of the Dawn, from the mischief of created things; From the mischief of darkness as it overspreads; From the mischief of those who practice secret arts; and from the mischief of the envious one as he practices envy’” (Quran 113:1–5).

The Talmud states:

“For one who dies of natural causes, ninety-nine die of an evil eye” (Rab. Talmud: Baba Metzia, 107b).

Bad juju. Bad energy. Negative energy. All delivered with an evil, envious gaze.

RED HORNS, GOLD AMULETS

According to Italian tradition, there are several methods to exorcise the malocchio. The primary method is the symbol I wear around my neck. I was given this charm, a gold horn, or cornicchio (pronounced “corn-e-que”), when I was fourteen years old. My grandmother was concerned I was smart and pretty. And in danger.

Other cultures use a red horn — which you may have seen. Still others use eye symbols, baths in the ocean, saliva in the person’s hair, potions, prayers, and so on.

At the time I interviewed my family, I wore my cornicchio without questioning my reasons. Cecilia, my mother, responded to my inquiry with,

“I don’t know why I wear it. In fact, it’s a bit of voodoo mixed with Catholicism, and if I were a ‘good’ Catholic, I wouldn’t. I do believe in God, but a simple prayer doesn’t — never seemed to do it. There seems to be more evil in this life than God. The cornicchio fights it. Why do I do it? Why do I have coffee for breakfast? It’s like the cross. It’s a symbol of my belief.”

Cecilia went on to tell me that the color red will also fight it. I know this because if any family member obtains a new car or a new house, grandma shows up with the holy water, a Saint Anthony medal, and red ribbon. Once grandma passed, the family took over the practice. I have little red ribbons in my drawers. In my car. Hanging in my closets.

When my husband and I purchased our car last month, we traded in our old car. My salesperson, Frank, asked if I had anything else to get from the trade in. I realized I had forgotten my red ribbon. Frank, also Italian, struggled to pull it from the gearshift so I would not drive off the lot without it.

By family vote (myself included), the color red is a strong color, bearing connotations of power. It also symbolizes the blood of Christ and the red robe he wore to his crucifixion. Wearing red may just make a person feel less at the mercy of the evil eye.

THE RITUAL

If you feel the need, you can choose the extensive, and often expensive, ritual. Josephine described the ritual in detail. You get a bowl of water and put seven drops of any oil in the bowl using the tip of your finger. Then you sprinkle the bowl with salt. Make the sign of the cross over the bowl and yourself while saying,

“Fuori malocchio, dentro buonocchio” (Out with the evil eye, in with the good eye.)

Then you go around the house with the bowl. If the oil spreads or dissipates, then there is evil. If it stays together — stays good — then there is no evil. The ritual is repeated two more times with five drops of oil and three drops of oil, respectively.

Josephine added that you can also get a priest or a gypsy to perform the ritual, but that the gypsies are usually crooks.

Big surprise, I thought. Like boardwalk psychics.

Why the oil and salt and water?

“Oil is the life of the family,” Josephine stressed. “So is the salt. These are staple foods…you couldn’t live without it. And salt gets rid of evil spirits.”

This seems to be logical, in a scary folk-science, superstitious way. If the oil goes “bad” in the bowl, the family would have problems with food and therefore things would not be going well. Perhaps you can appreciate the connection. Perhaps it’s nonsense.

MAKING SENSE

The cornicchio still remains a problem logically. Dominick had this to say:

“I got the horn on the chain… I keep it. Sure. In case it’sa true, I’ma protect. So far, no Malocchio from nobody. The cornicchio runs pretty good.”

I questioned further, mentioning that the “curnudo” or horns. You may have seen these as talisman. If you hold up your forefinger and pinky and close your other fingers, it resembles a bull’s horns. Held behind a man’s head meant the man’s wife was unfaithful. Dominick agreed this was true, yet protested the horn had the same strength at evil or to point out evil.

A horn of a bull symbolizes strength. A man who owned steer or bulls was more financially stable than one without. It can be inferred that the horn is a symbol of strength.

SIN?

These inferences and assumptions regarding the origins of this belief seem rational, yet the superstition is contrary to Catholicism. It is curious that the superstition has survived into the present, especially when Italians are known to be strictly Catholic. Many believe they control their own destinies and God has no negative interference, which would be the influence of the devil. The belief in the evil eye and its remedies seem to be a way to excuse the evil perceived in this world from God’s cause. He has nothing to do with it. It’s evil in humans. It’s the devil’s influence. Apparently, this is a human “fight” and cannot be solved with prayer or faith.

Cecilia commented, “I can’t fight it (the evil). I don’t even know if my horn works. If it did, I would have a hell of a lot better luck.”

Dominick added, “It’sa all bullashit.”

Yet, when prompted, neither would take the cornicchio off.

Cecilia laughed. “Why don’t you take yours off?”

I examined the little piece of gold against my fingertips. I thought, “I am not taking it off because it is a symbol that I will not be manipulated or attacked unawares by anyone at anytime. It is a symbol of strength.” That is the rationale. It is a symbol.

Yet, I am a strong, educated woman of good character. Shouldn’t that be enough?

Without explanation, my cornicchio stays right where it is.

And thank you for being such a faithful fan and reader. You’re a wonderful person. And just in case: God bless you.