Part 2 of 5: This article is the second article in a series prepared for The 13th Annual International Conference on the Image, “Here Comes the Metaverse: Designing the Virtual and the Real.” My presentation is entitled: Seeing is Believing: The Ethical and Legal Ramifications of Digital Image Manipulation.

As we continue our exploration into the ethics of image manipulation, I invite you to read the first article (alternative link) in this series if you have not done so. If you have already experienced that first episode, and appreciate the path we have taken together, proceed!

WHY THE DICTIONARY, PROFESSOR?

As you recall, I promised to explore the definitions of photography and image manipulation. A few of you contacted me and groaned: Why do we need this academic treatment?

Oh, but we do, grasshopper.

When we make choices or decisions — especially social, policy, ethics, and legal ones — we base those choices on values.The values we hold are based on what we believe to be true or not. Those beliefs are based on facts. At least what we consider facts. For example:

- If you believe a healthy body is likely to result in a longer life (medical fact), you will value a healthy diet and choose to exercise.

- If you believe owning a pet reduces stress (psychological fact), you will value having a cat, dog, fish, and so on. And you will have a pet or two (or three…).

- If you believe education is the key to success and a peaceful society (sociological fact), you will place education high on your priorities (value) and not only earn a degree, but also recommend others to do so.

Admittedly, however, facts can be slippery salamanders! Some professional psychologists proffer having a pet reduces stress; others offer opposing facts and do not agree. The key to understanding their disagreement is in the examination of the definitions they are using to reach their opposing conclusions. Perhaps the first group considers self-report of happiness to define stress-reduction. Perhaps the second group requires healthy blood pressure to define stress-reduction. Conflicts like these typically rest upon how each side defines the key terms.

We cannot decide and set policy for how to treat image manipulation if we do not decide the right and wrong of image manipulation. And we cannot decide the ethics and morality of image manipulation if we have yet to determine what is true about image manipulation. And we cannot determine what is true if we cannot agree on definitions. So, for our discussion, we must determine what is and what is not a photo and what is and is not image manipulation.

WHAT IS AN IMAGE?

When I ask this question, what is an image, I get odd, open-mouthed stares. I’m a photographer, right? I should know what a photo is, right? What an image is. Well, I do. And you do. Or we think we do.

A photograph is a depiction created by light registering on a photosensitive surface(like film or an electronic sensor). The word, from the Greek, means drawing with light. We call capturing light in this manner photography.

Yes, I know you know that. But: Note that the definition of a photograph is merely the recording of light. The pure definition does not include developing that recording to create an image. Non-digital photographs are developed using a chemical process to produce a negative. We then transfer the negative onto photographic paper, thus producing the positive picture. We process digital photographs using a computer to transform raw data into the picture.

We understand a picture to be a painting or a drawing or photograph. An imageis the likeness of an object reproduced on photographic material or a picture produced through an electronic display. So when a creator offers a picture, by definition, we cannot determine if it’s a drawing or photograph or digital art. We can say the same if the creator calls his or her work an image. We cannot determine how much change they effectuated after they captured the light.

In the vernacular, we understand photograph to mean an exact likeness. But we know an image can be an exact likeness or fantastical. That connotation is vital is differentiating between a manipulated and a pure image. We will discuss this concept in the next article, but for now, recognize when we examine a photograph, we expect it to be a likeness.

WHAT IS IMAGE MANIPULATION?

Manipulation means to change by artful or unfair means so as to serve one’s purpose. In the modern vernacular, image manipulation is defined as the transformation or alteration of an image to achieve desired results. Those desired results serve one’s purpose — and may be through unfair means. Although our gut reaction is to limit deceptive examples to digital art, where the image is obviously not an exact likeness, we are mistaken.

When a photographer captures an image, whether with film or with a digital camera, that image is either a negative (on film) or a RAW file (in digital). The image must be developed. Either on paper or in a digital file, the photographer uses methods to solidify an image. The photographer can alter the crop of the image. The exposure, white balance, and color can be manipulated. Photographers alter contrast and reduce haze. Photographers can dodge (brighten) or burn (darken) an image or a portion of the image. These are all examples of image manipulation.

We can, too, focus on the manner in which the photographer stages the image or selects the scene. Surely, a photographer manipulates the image as he or she sets up the shot. The photographer can include or exclude portions of the subject, alter the image through lens choice or position. These are decisions the photographer makes before pressing the shutter. For our purposes, we can ignore the capture of imagery. Those aspects are alternate conversations with separate issues. We can also set aside the presentation of images (including captioning) which alters the interpretation of what is depicted. That, too, is an alternate and important conversation. For our foray into this issue, let’s focus on post-capture manipulation.

Besides the basic edits to develop the image, the photographer can remove — or add elements. Adding a person. Removing a person. Removing power lines or a tree that distract from the composition. He or she can combine and stack images. He or she can completely alter color — turning a sky green. Acne or scars can be removed. Skin can be resurfaced. I can remove every wrinkle on a face!

Most of you reading this article are familiar with Adobe Photoshop and Lightroom. You may have used any number of photo editing software programs or apps. In fact, our mobile phones and computers have filters which easily add or subtract from our snapshots for uploading to social media. We can add cat ears and whiskers — or sparkles. We can change the focus to soft or increase the contrast. All with a button.

THE HISTORY AND RECEPTION OF IMAGE MANIPULATION

This type of photo manipulation is not new. Historically, image manipulation was used to restore old photographs or retouch images. Let’s remove the cat hair from that black shirt — or bring back the color to grandma’s fifty-year-old portrait. Alteration of the pure image was curative, not creative. Photography was a way to record what the eye had seen. Nothing more. And photography was dissimilar from the fine arts, where the painter crafts the work from nothing — from imagination or impression of what the eye captured. They accepted photography as a mechanical process that had nothing to do with creativity.

However, photographers from the first have manipulated images for creative — even deceitful — purposes.

For example, in 1864, a patriotic image depicted General Ulysses S. Grantleading his troops in the American Civil War. Except the image was a composite: (1) Grant’s head on (2) Major General Alexander M. McCook’s body — and horse, imposed on (3) the background of Fisher’s Hill, Virginia. Stalin and Mao Tse-Tung are infamous for manipulating enemies out of photographs. And Hitler was not to be undone when, for no apparent reason, he removed Joseph Goebbelsfrom images. Photographer-artists have altered election posters, heroic images, and battle images to suit the message.

And we wonder how the perpetrators slept at night.

Enter, the Photo-Secession movement, which esteemed Alfred Stieglitz established and promoted in the early 1900s. The movement argued photography was an art form. Experts celebrated image manipulation as a route to achieve a desired impact and produce the photographer’s subjective vision. This viewpoint emerged from the pictorial movement which compared a photographer’s tools (dodging, burning, cropping, focus, filters) with a painter’s brush strokes, paint, color choice, perspective, and so on. Photography was too long seen as strict reporting. Stieglitz and his associates argued photography was expressive, creative, and impactful. That photography was a distinctive medium of individual expressionand, as art, was, according to Brecht, not a mirror to reflect reality, but a hammer with which to shape it.

But the plot thickens.

As the promoter of pictorialism and father of the photo-secession movement, Stieglitz took a 180 and retracted his earlier assertions to argue the highest expression of photography was its ability to reflect reality. We call this approach straight photography. In this documentary style, the photographer’s role is to capture the emotion of the moment by photographing what the eye could see, eschewing pre and post manipulation. While the talented photographer could use lens choice and composition to present an image, straight photographers argued those efforts should faithfully reproduce and mirror the moment. Instead of using creative tools like a fine artist would, they would limit the photographer to his or her own preparation and creative use of a camera. No cropping and no manipulation, other than minor adjustments to exposure, were acceptable.

In Stieglitz, we find the ends of the spectrum and diametrically opposed ideas: photographic images as art to be manipulated in any manner to effectuate the creator’s vision versus photographic images as faithful documents and mirrors of reality. While these ideas are merely academic, for the most part, within those parameters we find images that are highly manipulated but presented as documentary. Therein lies our ethical dilemma, summarized in this entertaining video.

And ever-evolving technology hinders or outright defies our ability to tell reality from fantasy.

“Beauty is reality, truth is beauty, -that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” — Keats

ISSUE AWARENESS

Rightfully, any manipulation of the light collected on the film, plate, or censor fictionalizes the image. Experts assert that as long as the alteration of the image reproduces the perception of the scene, those alterations are merely processing, not manipulation. Recalculating exposure to correct to the original range the camera mis-recorded cannot be deemed manipulation. Correcting the white balance because the photographer forgot to set it in-camera cannot be deemed manipulation. Dodging, burning and other filters are similar to using a flash. What is the harm? The photographer is merely attempting to recapture detail he or she saw at that moment. And much of the manipulation photographers commit is innocent or incidental: Cropping out the distracting bush. Erasing grandpa’s nose hair. Eliminating the car that passed through the pristine landscape.

Juxtapose those edits with removing content of the picture that alters the impact of the picture. We have to ask: Who is the intended audience? What is the effect of the manipulation? What is the intent of the manipulation? Does the manipulation harm anyone? Is it sneaky or surreptitious? How dramatic is the manipulation?

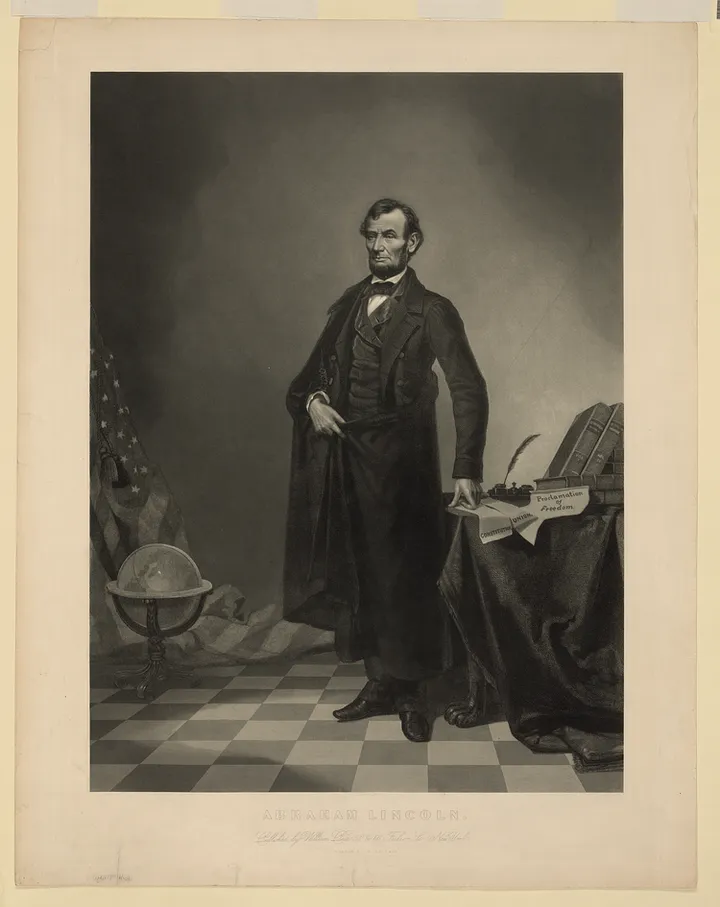

These questions have long plagued photographers and social scientists. As stated, dramatic image manipulation has not just emerged with today’s technology. Photographers have always been able to manipulate negatives. President Lincoln’s head was superimposed onto John C. Calhoun’s better-body to create an altered engraving (depicted at the top of this article). Similarly, Oprah’s head was superimposed onto Ann-Margret’s body (without either woman’s consent).

We are aware social media posters use beauty filters (Faceturn, FaceApp, and so on). We are painfully aware personalities manipulate images to appear in whatever manner they choose. Often ineffectually. We know the images we post and share can be stolen, and copyright infringed, by anyone who knows how to right-click and save or capture a screenshot. And we know the news is often fake.

In 1982, Gordon Gahan’s photo on the cover of National Geographic depicted two Egyptian pyramids to appear closer together than they actually are. The controversy brought the publication’s credibility into question and triggered one of the first debates about image manipulation. Tom Kennedy, replacement for the photography director who resigned after the controversy, stated: “We no longer use that technology to manipulate elements in a photo simply to achieve a more compelling graphic effect. We regarded that afterwards as a mistake, and we wouldn’t repeat that mistake today.”

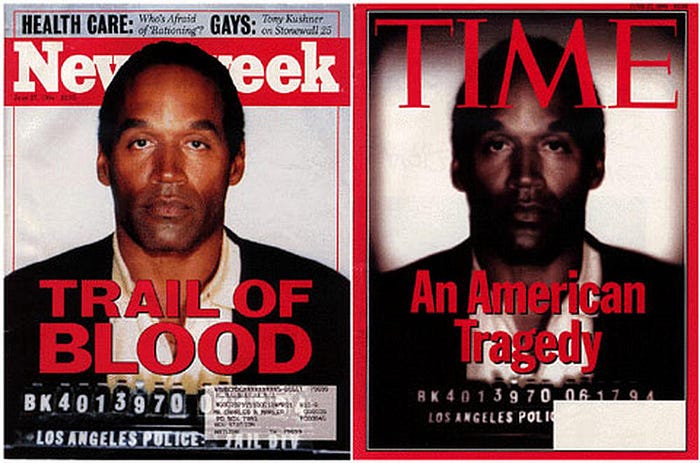

However, the National Geographic incident seems mundane and harmless when compared with TIME’s divisive OJ Simpson cover. In 1993, during the Simpson murder trial, both TIME and Newsweek published OJ Simpson’s mugshot as a cover image. However, TIME altered the photo to darken OJ’s skin — significantly. The public outcry was justifiably deafening.

We ask if the manipulation is merely developmental or artistic. We wonder if the image is deceptive. Or deceitful. Just this year, in the Depp-Heard defamation case, Amber Heard produced a photograph of her alleged injuries from her then-husband, Johnny Depp. Experts examined the photo, found incidences of image manipulation to enhance her injuries, and concluded Amber’s protestations of the photos being untouched were misrepresentations. Do we need to question the authenticity of proffered image evidence? Apparently, yes.

And we worry about how we can decipher the difference. Unlike digital manipulation, with film photography, an original negative remains as a permanent record. Unless the negative is destroyed, we can confirm the photo as unaltered. If we erase the metadata from a digital image, no record of the original remains.

SO WHAT?

After reading this article, you may conclude with So What? I thought the same for a long time. Until I dove into the subject and understood the spectrum of image manipulation. We will explore the dangerous impacts of image manipulation in the next article.

References are embedded within the article, and you can peruse the complete list of resources here.