Rather than begin our art history exploration with a severe and clinical examination of Roman architecture or the Surrealists, or some other academic topic, I thought we’d have some fun.

Everyone loves a compelling mystery, yes?

Well, the arts have some of the most incredible and exciting mysteries — and easily outshine the most popular reality crime drama. History’s mysteries include stories of pirates and hidden treasure. Lost artwork. Mysterious deaths. Unreadable manuscripts. Accusations of murder. Theft. Fraud.

And none are easily solved.

INVESTIGATIVE APPROACH

Unlike a modern crime mystery, historical mysteries are difficult to solve. We need to be an Indiana Jones, putting together clues that are often not straightforward.

We do want to use reliable and relevant evidence — and we don’t want to just jump to conclusions. An unscientific approach would cause Hercule Poirot to grumble with disdain. Yet, we do not often have direct evidence, like DNA or other physical evidence. Or correspondence. Or witness testimony.

Until we figure out how to swear-in dead people to testify, we have to rely on indirect evidence. Circumstantial evidence. Conjecture. Expert opinion. Related documents, perhaps. We rarely have a direct document or confession. And, due to the age of most of these questions, we never have photos, videos, or recordings.

The conclusions are inductive. Merely good guesses.

In the articles in this series, we will examine fine art mysteries, literature mysteries — and the most compelling art mystery surrounding The Bard. Get your magnifying glass, pocket notepad, and your decoder ring.

For our first mystery, we investigate Leonardo da Vinci’s mural, The Battle of Anghiari. Which may or may not exist.

In 1503, Italian statesman Piero Soderini commissioned da Vinci to decorate one wall of the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio (the town hall of Florence). The Salone (Hall of the Five Hundred) is a large auditorium (170 feet by 75 feet) meant for state gatherings, akin to the US Congress.

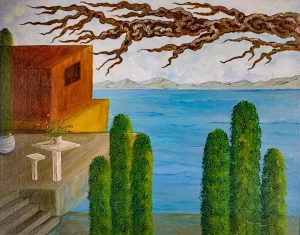

Da Vinci attempted to paint a reenactment of The Battle of Anghiari (Peter Paul Rubens’ version is depicted above). The 1440 battle against Milan was victorious for the Florentines, so to reproduce the image was a matter of state pride. But allegedly, when the oil paint wax mixture da Vinci used began to drip, he abandoned the project.

Reports say that around 1560, da Vinci fell out of favor with the royals–and artist Giorgio Vasari was told to paint over the murals. Vasari was so disturbed by having to do so, he allegedly covered da Vinci’s work with a false wall and then his own painting–The Battle of Marciano in Val di Chiana.

Researcher Maurizio Seracini of the University of California had been searching for the da Vinci mural and believed he would find it behind Vasari’s work. According to Seracini, Vasari left several clues to lead to the da Vinci masterpiece.

First, Vasari wrote highly about da Vinci’s piece. In his book Lives of the Most Excellent Paints, Sculptors, and Architects, Vasari said:

It would be impossible to express the inventiveness of Leonardo’s design for the soldiers’ uniforms, which he sketched in all their variety, or the crests of the helmets and other ornaments, not to mention the incredible skill he demonstrated in the shape and features of the horses, which Leonardo, better than any other master, created with their boldness, muscles and graceful beauty.

Second, Vasari’s The Battle of Marciano contains a green flag emblazoned with the words cerca trova — “he who seeks, finds.” Below, I provide the entire work and the enlarged section. Seracini decided it was a clue Vasari had left on purpose.

Seracini used non-invasive scanning systems (radar), drilled holes through the Vasari work, and searched with endoscopic camera probes. He claimed to have found black pigment identical to ones used in da Vinci’s other works. Critics chastised Seracini for drilling holes. The conflict resulted in stalled efforts when, in 2021, Italian authorities refused to allow the intrusion to continue.

In 2020, a group of art historians disputed Seracini’s claims and insist the da Vinci does not exist. They insist da Vinci was preparing the wall using a technique that would not work — so nothing exists but the prepared surface. Other critics dispute the meaning implied by Vasari’s flag. You can read details in Alex Greenberger’s ARTnews article.

You can watch the mystery unfold in the National Geographic Explorer, Season 26, Episode 13 documentary: Finding the Lost da Vinci.

On a side note, Michelangelo was commissioned to decorate the opposing wall but left the work incomplete when the Pope offered a more desirable commission.

The year is 1948. Hollywood producer and founder of 20th Century Fox, William Goetz, purchased Study by Candlelight for $50,000 ($500,000 in today’s money). He was told and was confident it was a Van Gogh.

Facts: The work appears to be a self-portrait. It appears to be signed on the verso. A notation stated the painting was swapped by Van Gogh for Japanese drawings. Another notation traced the ownership. A Van Gogh expert, Jacob de la Faille, verified its authenticity.

But after the Goetz purchase, the fun began. Another expert deemed it a fake — publically. Van Gogh’s nephew added his doubt. A jury of art experts examined the piece in 1949. They had it x-rayed. They examined the paint with microscopes. They compared brush strokes with known Van Gogh works. They checked the canvas, the threads of the canvas. And they said:

It’s not a Van Gogh. The paint strokes are all wrong — not like his work at all. And the paint density is all wrong. And the portrait itself was poorly done. And it didn’t “feel” like a Van Gogh.

Goetz and his family continued to represent it as a Van Gogh, and other experts supported their representation. But when it could not be sold (Sotheby’s refused because the value of the piece could not be determined), it was reevaluated in 2012. Still, its legitimacy was undetermined, and the controversy continues because other experts do not agree. Henk Tromp wrote an entire book on this ongoing mystery. It’s really quite a stir. Check out this video about this fascinating mystery.

When I lived in Boston, I spent my free time haunting every museum the city offers. On one of my outings, I became intrigued by the famous theft from the Stewart Gardner Museum.

On March 18, 1990, approximately 500 million dollars worth of artwork was stolen from the Gardner. Two men dressed as security guards duped the college desk clerk–and stole 13 works–the largest property crime in US history!

None of the stolen pieces have been recovered.

Among the stolen works:

I have pictured these here so you can keep an eye out. There’s a 10 million dollar reward…if you are so motivated. To start your investigation, watch This is A Robbery: The World’s Biggest Art Heist.

ART CRIMES

You may have become familiar with art theft from the film Monuments Men. The film fictionalized the real people from the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Program (MFAA), who recovered and returned priceless works stolen by the Nazis during World War Two.

I think you would be surprised at the number of artworks stolen and recovered each and every day. I know I was.

The Gardner mystery piqued my interest in learning about art crime. I recently read a great book — Priceless, by Robert K. Wittman–and was immediately hooked on the art-crime arena as part of my novel. Mister Wittman, a retired FBI art-crime investigator, gives a true-to-life perspective of the criminal networks–and of how severe art crime is. Did you know the FBI has an entire division dedicated to recovery of lost treasures? Check the FBI site for more information–and read Wittman’s book!

MYSTERY WITHIN

Sometimes the art itself contains the mystery.

Consider Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring. This piece is another example of a work of art inspiring a novel and a film by the same name. Vermeer, Dutch, painted during an explosion of famous artists — including Rembrandt. He began his career focusing on the popular styles — including painting religious scenes.

The painting is called a tronie — an informal portrait. Photographers call this type of pose a candid. The girl seems startled to turn and face the artist. Yet, we have no idea who the girl was. It’s believed it was his eldest daughter. But her gaze begs the question: Was she his lover? A servant? A family friend? Who she was influences how we interpret the painting.

Is her gaze is one of longing? Critics say yes. That the gaze is intimate. Only her lips are made up — which would have been inappropriate for a girl so young. The turban and robe are too large. The turban was associated with professional sex workers or foreigners. And if the robe is not hers, why is she wearing it? How about the pearl earring? Is it a pearl or metal? How would a poor or middle class girl have such a piece of jewelry? And the black background takes her completely out of a scene — we don’t even know where she is!

Take a moment and theorize who she may have been. I’m a Vermeer fan — and the painting is one of my favorite pieces, not only for its beauty but also for its mystery.